It sucks fluid out of astronaut’s heads and toward their feet.

Being an astronaut demands excellent 20/20 vision, yet the impacts of space can cause astronauts’ eyesight to deteriorate, causing them to return to Earth with impaired vision. Researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center have developed a sleeping sack that can avoid or decrease these issues by sucking fluid out of astronauts’ brains.

More than half of NASA astronauts who spent more than six months on the International Space Station (ISS) had visual impairments of various severity. According to the BBC, astronaut John Philips returned from a six-month mission aboard the International Space Station in 2005 with his vision diminished from 20/20 to 20/100.

- Microsoft attempted, but failed, to bring Xbox games to the App Store for iOS.

- Forbes has recognized my achievements. — Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo

For multi-year trips to Mars, for example, this could become an issue. “It would be a disaster if astronauts had such severe impairments that they couldn’t see what they’re doing and it compromised the mission,” lead researcher Dr. Benjamin Levine told the BBC.

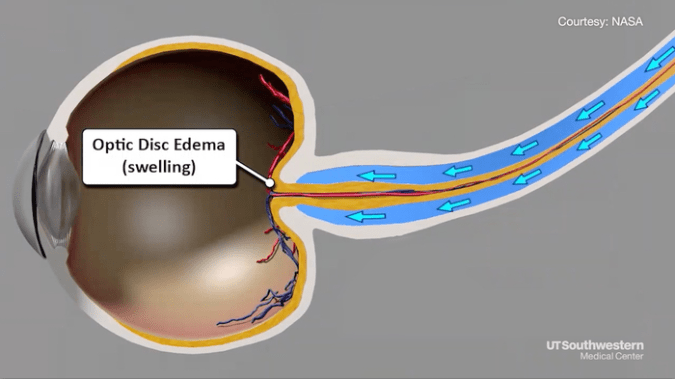

Fluids tend to accumulate in the head when you sleep, but on Earth, gravity pulls them back down into the body when you get up. In the low gravity of space, though, more than a half gallon of fluid collects in the head. That in turn applies pressure to the eyeball, causing flattening that can lead to vision impairment — a disorder called spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome, or SANS. (Dr. Levine discovered SANS by flying cancer patients aboard zero-G parabolic flights. They still had ports in their heads to receive chemotherapy, which gave researchers an access point to measure pressure within their brains.)

To combat SANS, researchers collaborated with outdoor gear manufacturer REI to develop a sleeping bag that fits around the waist, enclosing the lower body. A vacuum cleaner-like suction device is then activated that draws fluid toward the feet, preventing it from accumulating in the head.

Around a dozen people volunteered to test the technology, and the results were positive. Some questions need to be answered before NASA brings the technology aboard the ISS, including the optimal amount of time astronauts should spend in the sleeping bag each day. They also need to determine if every astronaut should use one, or just those at risk of developing SANS.

Still, Dr. Levine is hopeful that SANS will no longer be an issue by the time NASA is ready to go to Mars. “This is perhaps one of the most mission-critical medical issues that has been discovered in the last decade for the space program,” he said in a statement.